What’s a Rep?

When defining a repetition (rep), we might define it as the completion of an action. The definition describes what a rep is. It doesn’t describe the quality of that rep. As strength coaches, we need to define the quality of what a rep is in order to have a model of movement efficiency. We also must understand the development of a proper rep as it exists in the motor learning process.

Motor Learning

Here are my thoughts on motor learning related to the supervision and autonomy…we allow a rep to have.

When I monitor my athletes’ development or motor learning, I follow the principle of variability. What I mean by this is that when a rep is performed, although it may look extremely similar to the previous rep, it will have variability. The variability is created from ever so slightly inconsistent balance, shifting of weight, proprioceptive feedback, and so on. This variability, grown from a solid pattern, provides greater options, or as often calls it… “Bandwidth.”

First, the rep needs to be performed in such a manner that it fits into my model of movement for the skill or pattern. Secondly, once the pattern has “grown some roots”, it can allow variability to establish more options for the athletes. These options allow the athlete to complete a rep with less than optimal form at times, and still be safe and effective. Consider the alternative of the athlete unable to manage a disturbance in their pattern, they crash and burn. As Gary Gray has said many times, I’m paraphrasing, ”If you’ve been there and done that, then it is not a surprise, and you know how to handle it.” Great athletes typically have more options to manage each rep or movement pattern.

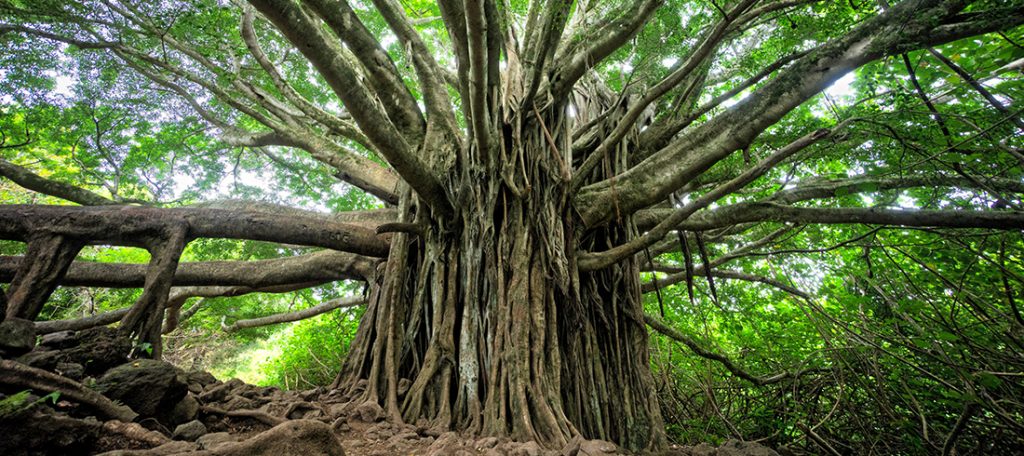

Newly planted trees will quickly begin to grow roots into the ground. Initially these roots are small, not very deep, or wide. Over time the roots not only grow deeper but also wider. The depth of the roots gives strength and stability, while the width gives variability and options to “feed” the tree. A rep needs roots too!

In the early stages of motor learning, the rep is very unstable and certainly has few options or variability. With time and intent, the rep grows its roots deep and wide. With time and intent, motor learning becomes established, too.

A great example of this is when a child learns to ride her bike. Over time she moves from a wobbly accident waiting to happen, to a sturdy rider able to look around, avoid obstacles, and possibly ride with no hands. Her motor learning roots become deeper and wider with each ride.

Another aspect of the motor learning process and the development of a rep is when an athlete learns a new pattern. He or she will create a schema of this pattern. It happens with trial and error and just enough feedback from the coach to keep it safe and on track. An implicit learning style can often lead to a skill or pattern configuration that becomes strong and variable. This can be tricky at times. A coach must have a pulse if the athlete is developing poor patterning. If this is the case, the coach must quickly redirect through coaching strategies, such as cuing. Learning takes time and requires the reps to build a deep and wide root system to handle variation.

Trial and Error

If we were to simply look at learning and becoming better strictly through the lens of human development, meaning as the athlete becomes older and has more experience with reps, the better they become. We would then find trial and error and proper completion of a task drives the learning experience. There is a reason fourth graders are better than third graders and fifth graders are better than fourth graders. They’ve had time to grow deeper and wider roots than the younger, less experienced athlete. If we combine proper coaching with this natural event of human development, we can create environments where reps build roots.